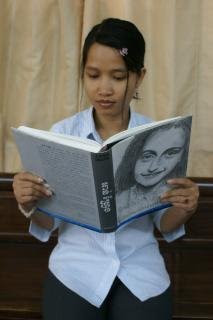

Sayana Ser reads a copy of the Khmer translation of the "The Diary of a Young Girl" by Anne Frank. Photo by Tibor Krausz.

Sayana Ser reads a copy of the Khmer translation of the "The Diary of a Young Girl" by Anne Frank. Photo by Tibor Krausz.The Wisconsin Jewish Chronicle

By Tibor Krausz

Phnom Penh, Cambodia (JTA) — As a young girl in the early 1990s, Sayana Ser often spent the night cowering in fear with her family in an underground shelter her father had dug beneath their home on the outskirts of this capital city.

Outside, marauding bands of Khmer Rouge guerrillas battled it out with government forces. Meanwhile, brutal mass murder was still fresh on civilians’ minds.

A decade later, as a 19-year-old scholarship student in the Netherlands, Sayana chanced upon the memoirs of another girl who had feared for her life in even more dire circumstances.

It was “The Diary of a Young Girl” by Anne Frank, the precocious Jewish teenager who hid from the Nazis in occupied Amsterdam until her family’s hiding place was discovered and she was sent to her death in the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp.

“While reading the book I couldn’t hold my tears back,” Sayana recalls. “I wondered how Anna must have felt and how she could bear it.”

Sayana now is the director of a student outreach and educational program at a Cambodian research institution that documents the Khmer Rouge genocide. Between 1975 and 1979, up to 2 million people — a fourth of the population — perished on Pol Pot’s “killing fields” in one of the worst mass murders since the Holocaust.

Sayana, who wrote her master’s thesis about “dark tourism,” or touristic voyeurism at genocide sites in Cambodia and elsewhere, also visited several Holocaust memorials and death camps.

“I couldn’t believe how one human being could do this to another, whether they were Jews or Khmers,” she says.

On returning home, she sought permission to translate the Anne Frank diary into Khmer.

The Holocaust classic was published by the country’s leading genocide research group, the Documentation Center of Cambodia. It is now available for Khmer students at high school libraries in Phnom Penh alongside locally written books about the Khmer Rouge period.

Such books include “First They Killed My Father” by Loung Ung, which recounts the harrowing experiences of a child survivor of the killing fields.

Next to Laos

“I have seen many Anna Franks in Cambodia,” says Youk Chhang, the head of the documentation center and Cambodia’s foremost researcher on genocide.

A child survivor himself, Chhang lost siblings and numerous relatives in the mass murders perpetrated by Pol Pot and his followers.

“If we Cambodians had read her diary a long time ago,” he says, “perhaps there could have been a way for us to prevent the Cambodian genocide from happening.”

Anne Frank’s message, he adds, remains as potent as ever.

“Genocide continues to happen in the world around us even today,” Youk says. “Her diary can still play an important role in prevention.”

Although the story of Anne and her resilient optimism in the face of murderous evil has touched millions of readers around the world, it may particularly resonate with Cambodians, Sayana adds.

“Under Pol Pot, many children were separated from their families. They faced starvation and were sent to the front to fight and die,” she explains. “Like Anna, they never knew peace and the warmth of a home.”

Inspired by Anne’s diary, she adds, some Cambodian students have begun to write their own diaries to chronicle the sorrows and joys of their daily lives.

Children in Laos, too, can soon learn of Anne’s story and insights.

In the impoverished, war-torn communist country bordering Cambodia, almost a million people perished during the Vietnam War, while countless landmines and a low-level insurgency continue to take lives daily.

Yet with books for children almost nonexistent beyond simple school textbooks, Lao students remain largely ignorant of the world and history. In a private initiative, an American expat publisher is now bringing them children’s classics translated into Lao, including Anne Frank’s diary.

“I was describing the book to a bright college graduate here and gave him a little context,” says Sasha Alyson, the founder of Big Brother Mouse, a small publishing house in Vientiane, the Lao capital, which specializes in books for Lao children. He recalls the student asking, ‘World War II? Is that the same as Star Wars?”

Anna Frank’s “Diary of a Young Girl,” he says, will provide Lao children with a much-needed lesson in history.

By Tibor Krausz

Phnom Penh, Cambodia (JTA) — As a young girl in the early 1990s, Sayana Ser often spent the night cowering in fear with her family in an underground shelter her father had dug beneath their home on the outskirts of this capital city.

Outside, marauding bands of Khmer Rouge guerrillas battled it out with government forces. Meanwhile, brutal mass murder was still fresh on civilians’ minds.

A decade later, as a 19-year-old scholarship student in the Netherlands, Sayana chanced upon the memoirs of another girl who had feared for her life in even more dire circumstances.

It was “The Diary of a Young Girl” by Anne Frank, the precocious Jewish teenager who hid from the Nazis in occupied Amsterdam until her family’s hiding place was discovered and she was sent to her death in the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp.

“While reading the book I couldn’t hold my tears back,” Sayana recalls. “I wondered how Anna must have felt and how she could bear it.”

Sayana now is the director of a student outreach and educational program at a Cambodian research institution that documents the Khmer Rouge genocide. Between 1975 and 1979, up to 2 million people — a fourth of the population — perished on Pol Pot’s “killing fields” in one of the worst mass murders since the Holocaust.

Sayana, who wrote her master’s thesis about “dark tourism,” or touristic voyeurism at genocide sites in Cambodia and elsewhere, also visited several Holocaust memorials and death camps.

“I couldn’t believe how one human being could do this to another, whether they were Jews or Khmers,” she says.

On returning home, she sought permission to translate the Anne Frank diary into Khmer.

The Holocaust classic was published by the country’s leading genocide research group, the Documentation Center of Cambodia. It is now available for Khmer students at high school libraries in Phnom Penh alongside locally written books about the Khmer Rouge period.

Such books include “First They Killed My Father” by Loung Ung, which recounts the harrowing experiences of a child survivor of the killing fields.

Next to Laos

“I have seen many Anna Franks in Cambodia,” says Youk Chhang, the head of the documentation center and Cambodia’s foremost researcher on genocide.

A child survivor himself, Chhang lost siblings and numerous relatives in the mass murders perpetrated by Pol Pot and his followers.

“If we Cambodians had read her diary a long time ago,” he says, “perhaps there could have been a way for us to prevent the Cambodian genocide from happening.”

Anne Frank’s message, he adds, remains as potent as ever.

“Genocide continues to happen in the world around us even today,” Youk says. “Her diary can still play an important role in prevention.”

Although the story of Anne and her resilient optimism in the face of murderous evil has touched millions of readers around the world, it may particularly resonate with Cambodians, Sayana adds.

“Under Pol Pot, many children were separated from their families. They faced starvation and were sent to the front to fight and die,” she explains. “Like Anna, they never knew peace and the warmth of a home.”

Inspired by Anne’s diary, she adds, some Cambodian students have begun to write their own diaries to chronicle the sorrows and joys of their daily lives.

Children in Laos, too, can soon learn of Anne’s story and insights.

In the impoverished, war-torn communist country bordering Cambodia, almost a million people perished during the Vietnam War, while countless landmines and a low-level insurgency continue to take lives daily.

Yet with books for children almost nonexistent beyond simple school textbooks, Lao students remain largely ignorant of the world and history. In a private initiative, an American expat publisher is now bringing them children’s classics translated into Lao, including Anne Frank’s diary.

“I was describing the book to a bright college graduate here and gave him a little context,” says Sasha Alyson, the founder of Big Brother Mouse, a small publishing house in Vientiane, the Lao capital, which specializes in books for Lao children. He recalls the student asking, ‘World War II? Is that the same as Star Wars?”

Anna Frank’s “Diary of a Young Girl,” he says, will provide Lao children with a much-needed lesson in history.

No comments:

Post a Comment